VI. The Great Metaphysics Conspiracy

When Aristotle got circumsized; Why Aquinas feared werewolves, and How Maimonedes' waged war against gentile sorcery.

We left off talking about Aristotle, but we didn’t really get too deep into his ideas. I was trying to spice things up with my mystery caper to set the stage first. If you haven’t read it yet, here you go, it is a fun read:

V. The Great Metaphysics Conspiracy

I want to dedicate the fifth entry in the Metaphysics Conspiracy series to an ancient conspiracy yarn which highlights the political implications of all of our metaphysical speculation in previous essays.

Today we have to pick up and get into the damage that Aristotle did with his actual philosophizing. Before you start yawning let me acknowledge that yes, Aristotle is extremely boring. I confess that I’ve mostly just read around him myself. It was not for lack of trying though! We were supposed to read some of him in high school and then in college and only finally, when I was trying to study the roots of the West’s nihilistic anti-mystical “rationalism” did I finally understand how important a figure he was.

Yes, Aristotle fits right into our emerging Helleno-Hebraic anti-metaphysics conspiracy theory.

Do you still remember the key thesis to this series by the way? Let me remind you since it has been a long time since the last installment.

Put simply: there was a plot to do away with mysticism started by Plato and continued through Helleno-Hebrewism and the later so-called European Philosophical Tradition as well. The most modern and up to date version of this long-running program can be called Scientism™ , which is what we suffer under today, mostly because of the Anglo Empire. It is the most radical form of atheism that we have experienced in the world to date where pretty much all non-material realities are now denied by polite society. What is worse, the majority of the population, at least in the West, accepts these terms unquestioningly because of their loyalty to the current or previous iterations of the same revolutionary program like Communism or Christianity, which are built on the same core assumptions.

And if the metaphysics plot got its start with Plato, well it develops its “scientific” anti-mystical totalitarian dimension under Aristotle, which makes him well worth discussing. Before the scientists came along though, Aristotle first had to be integrated into the Judeo-Christian project and this was accomplished with Maimonedes and Aquinas.

Does all of that make sense as a primer for the essay? Gosh, I sure hope so.

We’ve covered a lot of the Greek political background to Aristotle in the previous piece. But now we have to suddenly jump into the future a few centuries to the so-called “12th” century in Europe to pick up our story with Aristotle. According to the standard chronology, Aristotle’s ideas were only picked back up after being lost for more than a thousand years and brought back to Europe thanks to translated Arabic texts making their way over from Syria and the wider Middle East in the wake of the Crusades.

In reality, we now know that many extra centuries were tacked onto the first millennium by the Catholic Church.

Red List 32 - The Fake First Millennium w/ Laurent Guyenot

Many thanks to Laurent for sharing his research with me! You can get his new book Anno Domini: A Short History of the First Millennium AD here! It is FASCINATING! Go do it now!

But I am not going to get into alternative timelines or abstract political theory in this piece. Instead I will simply rely on the conventional narrative regarding the development of Western thought to prove my point. That being said, I’m going to bring up some information I am 100% sure that my readers have never heard of before.

Aquinas is traditionally explained in Western universities as being one of the defining figures in Western history. He allowed the Western mind to start a process that would pull it ahead of the rest of the world and then eventually subjugate it via its empires. This is because Aquinas is credited with introducing Aristotle to Christianity i.e., allowing science back into the West by rehabilitating a pagan philosopher, thereby tempering the Abrahamic dogmatism of Christianity which had led Europe into stagnation.

Aristotle was also the only pagan philosopher that was compatible with Judeo-Christian dogma other than Plato. Thus, his concept of using logic and empirical experimentation to puzzle out the nature of material reality did not clash with Abrahamism. Other pagan thinkers let their metaphysical speculations about the underlying nature of higher realities inform their more earthly scientific views. The heavens influenced everything in our world and our world influenced the heavens (as above, so below; as below, so above) in the pagan worldview and so metaphysics and regular science or the study of material reality were intertwined.

This, however, was not a problem with Aristotle, who was an iconoclast, anti-pagan monotheist to boot.

Thus, just as Aristotle was rehabilitated, so too was the concept of science, which had hitherto been seen as superfluous at best (why bother with science when all the truths of the world are contained in the Bible?) or blasphemous at worst.

For an overview see here:

Ironically, Aristotle ended up being brought back into the fold of the meta-conspiracy (Abrahamism) that Aristotle had ironically played a part in engineering in the very first place. Like a dog returning to its own vomit, the medievals had rediscovered their original prophets somehow. Symbol wise, imagine a snake eating its own tail. Better yet, recall what I have written about how each so-called “revolution” in thought or ideology has actually been a reversion to fundamentalism and is part of a permanent cycle of reinforcing, course-correcting social engineering …

Aristotle’s Post-Mortum Conversion to Judaism

Right off the bat, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out just how highly Aristotle was held in regard by Abraham’s people. This should set off some alarm bells in the mind of the reader and if it doesn’t then I simply haven’t done a very good job as a blogger up to this point. I’m going to be quoting the Jewish Encyclopedia for this part (their own writings on the matter) so this is hardly fringe conspiracy territory that we’re in here, but the actual, literal definition of kosher, mainstream history.

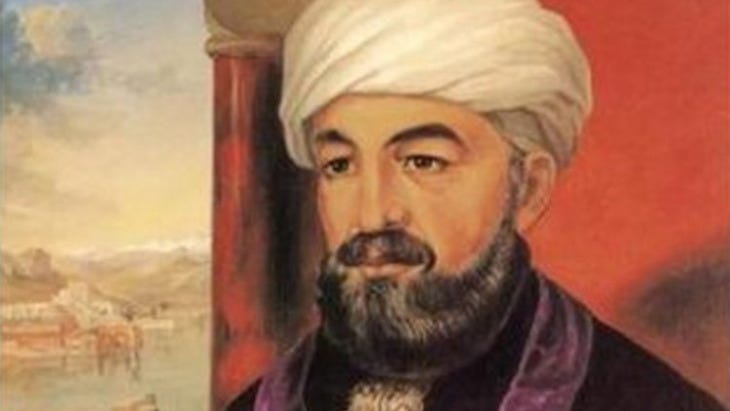

Let’s just start here with Rabbi Maimonedes:

Aristotle's influence upon Jewish thinkers, however, varied in different ages. Abraham ibn Daud (1160) was the first Jewish philosopher to acknowledge the supremacy of Aristotelianism. Earlier thinkers unquestionably were acquainted with Aristotle's philosophy, but the systems of Plato and other pre-Aristotelian philosophers then held the field. From Abraham ibn Daud until long after Maimonides' time (1135-1204), Aristotelian philosophy entered and maintained the foreground, only again to yield its position gradually to Platonism, under the growing influence of the Cabala.

Yeah, so, the Kabbalah was created out of Neoplatonism, which was a mix of Plato’s ideas and “magic” sprinkled in. But that’s a topic for the next essay, sorry. Aristotle began to eclipse Plato in his popularity as the middle ages went on for reasons that will become more and more apparent as we dig deeper in this essay.

In the period following Gabirol, the writings of Avicenna, a commentator upon Aristotle, became widely known throughout Europe, leading to the displacement of the older philosophy based upon Plato and Neo-Platonism. The Arabic expounders of Aristotle leavened his views more and more with monotheism; and thus through new interpretations and constructions the heathen character of his philosophy was gradually refined away. Then, too, many works passed under Aristotle's name that a more critical age would immediately have detected as spurious. But the lack of all critical sense in the Middle Ages, and the general prejudice in favor of Aristotle, whose genuine writings contain many passages in which he rises from heathenism to almost pure monotheism, blinded even the most discerning to the fact that many of the works ascribed to him could not possibly have been his. The most important works of this character are "Aristotle's Theology" (ed. by Dieterici) and "Liber de Causis" (ed. by Bardenhewer). Modern scholars have discovered the former to be a mere collection of extracts from the "Enneades" of Plotinus; in the Arabic version of which passages antagonistic to monotheism are paraphrased or entirely omitted. Similarly the "Liber de Causis" is nothing but an extract from the Στοιχείωσίς θεωλογικη by Proclus.

No man has been so beloved by the Hebrewish people since Donald Trump or Vladimir Putin, probably. It was Maimonides, probably the most important rabbi of all time that first sees just how valuable Aristotle is for his people and their agenda. This is the man who basically created and codified the Talmudic tradition (Jewish Theology/Hebrew Catechism),

I will explain more later in the essay.

Aristotle was almost universally held in esteem by the Jews; at one time for his intelligence and mental power, at another as a penitent sinner. The following is Maimonides' verdict concerning him: "The words of Plato, Aristotle's teacher, are obscure and figurative: they are superfluous to the man of intelligence, inasmuch as Aristotle supplanted all his predecessors. The thorough understanding of Aristotle is the highest achievement to which man can attain, with the sole exception of the understanding of the Prophets." Shem-Ṭob ben Isaac of Tortosa (1261) styles Aristotle "the master of all philosophers." Elijah b. Eliezer of Candia, who edited the "Logic" about the end of the fourteenth century, calls Aristotle "the divine," because, having been endowed by nature with a sacredly superior intellect, he could understand of himself what others could receive only from the instruction of their teachers.

In other words, what the Hebrews had received through divine revelation via Moses, Aristotle had somehow reasoned out on his own using his logic.

What. A. Coincidence!

Of course, we now understand that the similarity of the Bible to Aristotle isn’t because the two came to similar conclusions independent of one another, but because the Bible writers were Helleno-Hebrews in Alexandria that were working with Plato and Aristotles’ philosophy to create a new religion! See Gmirkin’s work in my previous series entries.

We continue:

While the Arabs preferred Aristotle's logical and metaphysical works, Maimonides devoted his attention to his moral philosophy and sought to harmonize it with revelation.

(…)

This theory of moral theology is the introduction to Maimonides' philosophical system as presented in the "Moreh Nebukim" (Guide for the Perplexed). Following generally in the footsteps of Aristotle, he deserts him only when approaching the domain of God's law. But here, too, it is Aristotelian doctrine, coinciding, it is true, with Revelation in the basic principle that men are incapable of comprehending God's being fully, on account of their imperfection and His perfection. Concerning the sphere of metaphysical thought, absolute truth must lie in Revelation; that is, in Judaism.

All that Plato and Aristotle thought out had been already correctly and more deeply taught by the philosophical oral law, of the possession of which by the Prophets Maimonides is convinced ("Moreh," i. 71, ii. 11).

Yes, another coincidence!

While everything that Aristotle wrote concerning nature, from the moon down to the center of the earth, was founded upon positive proof and is therefore sure and irrefragable, all his ideas concerning the character of the higher spheres partake rather of the nature of opinions than of philosophical certainties ("Moreh," ii. 22).

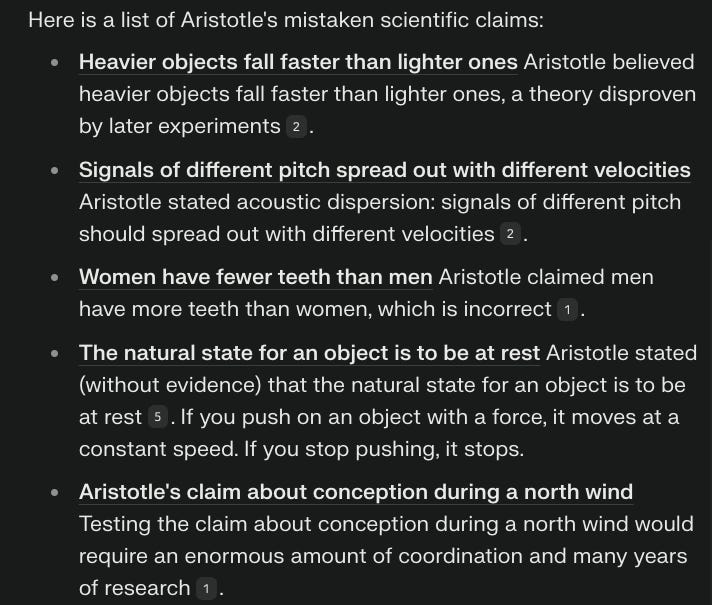

As it turns out though, literally ALL of Aristotles’ science claims ended up being wrong because he just made them all up. Here is the non-exhaustive list (a sampling) just in case you don’t believe me:

Aristotle just goes on and on with this “scientific” nonsense.

What is worse, Aristotle is literally considered (and taught in schools) as a kind of pioneering scientific crusader against superstition, despite the fact that he promulgated beliefs that we would consider superstitious nonsense nowadays. The narrative believed by just about everybody who superficially studies this kind of thing is that before Plato and Aristotle, we (Europeans) shared a culture that was similar to all other peoples in the world. It was only thanks to these two that we invented philosophy, became “rational” and broke free of our dark, superstitious past of our primitive ancestors.

…

Let us finish up with Maimonedes and his crush on Aristotle:

Aristotle was almost universally held in esteem by the Jews; at one time for his intelligence and mental power, at another as a penitent sinner. The following is Maimonides' verdict concerning him: "The words of Plato, Aristotle's teacher, are obscure and figurative: they are superfluous to the man of intelligence, inasmuch as Aristotle supplanted all his predecessors. The thorough understanding of Aristotle is the highest achievement to which man can attain, with the sole exception of the understanding of the Prophets." Shem-Ṭob ben Isaac of Tortosa (1261) styles Aristotle "the master of all philosophers." Elijah b. Eliezer of Candia, who edited the "Logic" about the end of the fourteenth century, calls Aristotle "the divine," because, having been endowed by nature with a sacredly superior intellect, he could understand of himself what others could receive only from the instruction of their teachers.

It was also Maimonides who came up with the legend that Aristotle was secretly circumsized because of how compatible his views were with the Torah.

Here:

In the circles where the antagonism of Judaism and Hellenism was known and understood, Aristotle was reported by tradition to have said: "I do not deny the revelation of the Jews, seeing that I am not acquainted with it; I am occupied with human knowledge only and not with divine" (Judah ha-Levi, "Cuzari," iv. 13; v. 14). But when Aristotelianism became harmonized with Judaism by Maimonides, it was an easy step to make Aristotle himself a Jew. Joseph b. Shem-Ṭob assures his reader that he had seen it written in an old book that Aristotle at the end of his life had become a proselyte ("ger zedeḳ"). The reputed statement of Clear-chus is repeated by Abraham Bibago in the guise of the information that Aristotle was a Jew of the tribe of Benjamin, born in Jerusalem, and belonging to the family of Kolaiah (Neh. xi. 7). As authority for it Eusebius is cited, who, however, has merely the above statement of Josephus.

According to another version, Aristotle owed his philosophy to the writings of King Solomon, which were presented to him by his royal pupil Alexander, the latter having obtained them on his conquest of Jerusalem. With this legend of Alexander is associated the celebrated "Letter of Aristotle" to that monarch. Herein Aristotle is made to recant all his previous philosophic teachings, having been convinced of their incorrectness by a Jewish sage. He acknowledges as his chief error the claim that truth is to be ascertained by the reasoning faculty only, inasmuch as divine revelation is the sole way to truth. This "letter" is the conclusion of an alleged book of Aristotle, "two hands thick," in which he withdraws, on the authority of a Jew, Simeon, his views with regard to the immortality of the soul, to the eternity of the world, and similar tenets. The existence of this book is mentioned for the first time about 1370 by Ḥayyim of Briviesca, who expressly declares that he heard from Abraham ibn Zarza that the latter received it from the vizir Ibn al-Khatib (d. 1370). He does not state whether this apocrypha was written in Arabic or Hebrew; the Hebrew "Letter," as received, does not appear like a translation. It is safe to assume with Ḥayyim, that the Simeon mentioned was none other than Simeon the Just, about whose supposed relations to Alexander the Great the oldest Jewish sources give us information (Yoma, 69a; see Alexander the Great). Identical with this letter is the prayer of Aristotle which the Polish BaḦurim had in their prayer-books during the sixteenth century (Isserles, Responsa No. 6; ed. Hanau, 10a.

A second "Letter" by Aristotle to Alexander contains wise counsel on politics; he advises the monarch that he must endeavor to conquer the hearts, and not simply the bodies, of his subjects (preface to "Sod ha-Sodot"). See Samter, "Monatsschrift," (1901) p. 453.

The essay entitled "The Apple," also ascribed to Aristotle, is tinged with a similar tendency. In it Aristotle refers to Noah and to Abraham, "the first philosopher." It was these spurious writings of Aristotle which gained for him the esteem of the cabalists, as evidenced by the very flattering utterances of Moses Botarel (Commentary on "Yeẓirah," 26b). The story of the love-affair between Aristotle and Alexander's wife, in which the former comes off very badly—current in the Middle Ages (see Peter Alfonsi, "Disciplina Clericalis," vii.) and originating in a Hindoo fable (see "Pantschatantra," ed. Benfey, ii. 462)—was also told in Jewish circles, and exists in manuscript by Judah b. Solomon Cohen (thirteenth century), in Spirgati's catalogue, No. 76 (1900), p. 18.

And that is the secret story of how Aristotle was converted to Judaism after his death.

(…)

We can explain why Aristotle’s philosophy and approach to science so appealed to the later Abrahamic social engineers and how it relates to the themes of this essay series by simply studying what the great Thomas Aquinas thought of Aristotle’s work and why it became so key to all Western thinking from that point onwards. This approach will prove that I am not providing my own idiosyncratic reading of Aristotle, but that I am using the mainstream interpretation of his theories.

I should have done this with Plato as well, because I may have left the impression that I was simply telling my view on Plato when in reality, I was simply providing the mainstream consensus on Plato’s war against “superstition” that centuries of thinkers have since picked up on and built off of.

The Mystical Deception of Thomas Aquinas

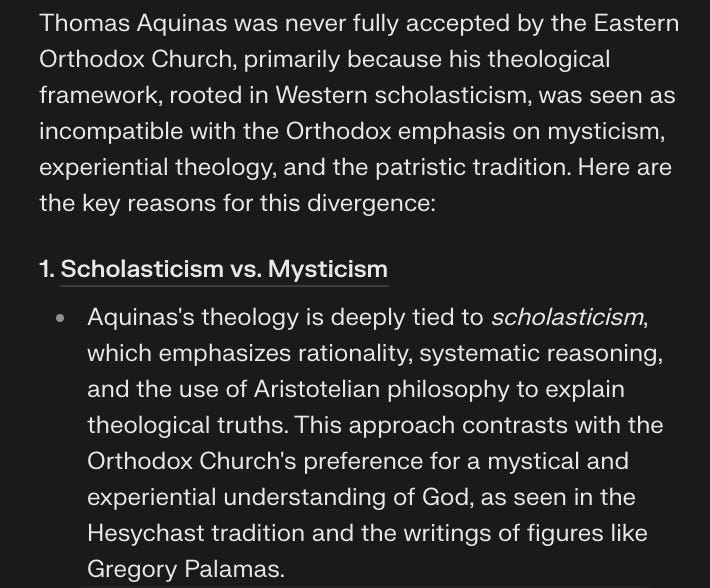

It was thanks to Aquinas that Western/Latin Christianity began its major divergence from the East. There were other key moments like the establishment of the primacy of the Papacy of Rome or the Gregorian monk coup (which led to holy days being celebrated on different days thanks to the new calendar), but Aquinas was one of the most significant divergences between what became known as Catholicism and Orthodoxy.

Boiled down to its most essential, Aquinas invented Catholic theology as we know it now by rejecting mysticism and replacing it with logic (of a kind), which was then codified into theology over the centuries. Some refer to this as Logos Theology; more on that a bit later:

Once again, let me emphasize that this isn’t me sharing my strange, unique interpretation of events, as my critics like to accuse me of doing. This is a core Orthodox claim, and it was from studying Orthodox beliefs that I learned about the perfidy of Aquinas in the first place.

Long-time readers know that I used to be a student of Hesychasm, the mystical Orthodox practice of the monks of Mt. Athos and Valaam.

Reactionary Metaphysics I: Faith vs Knowing

We’re entering a new and exciting field of inquiry with its own jargon, assumptions and lore. There are volumes dedicated just to debating proper etymology and epistemology within this field. Questions like: what is a soul? A spirit? And so on are still a matter of debate and definition. But I’m going to side-step all that as best I can and endeavor to …

What very few know is that the main doctrinal dispute between Orthodoxy and Catholicism was actually over the issue of mysticism. It came to a head in the 14th century, at the famous heresy trial of the Hesychasts in which they were accused of being demon-worshippers by the Latin church. The famous Orthodox lawyer Gregory Palamas was commissioned by the Greek Emperor to defend the monks (for political reasons, no doubt) and this set in stone the main divergence in Christian thought between West and East.

The West would go the route of Aristotelian-Aquinasty, while the East would remain “mired in superstition” for centuries more, as the standard Western narrative goes that is.

I want to make sure that readers understand what was decided at the trial and set into motion by Aquinas beforehand.

For as long as there have been conscious human beings, the concept of mysticism and the institution of religion have been intertwined. Mysticism to religion was like test tubes and bunsen burners to chemistry. Or guns and swords and spears to war; pots and pans to cooking and so on. Mysticism was the thing that you did or needed to use to do religion correctly.

What was the nature of life after death?

The will of the spirits?

The reason for the stars turning in the heavens?

The answers to those questions were traditionally arrived at via various “hands on” mystical practices of a magical nature. Religion in its more “primitive” state didn’t need theologies and institutionalized priesthoods, really. So long as the folk knew how to enter altered states and interact with the higher realms via dream states/theta states/astral projection, they could always bootstrap their own religion from the ground up based on their own visions and the metaphors or concepts that they derived from them. To have a religion without mystical rites was to practice a kind of atheism at the time, which was radical and subversive. Perhaps you will recall that I tried to explain the significance of Plato demanding a total ban on Titanic/Dionysian rites of the common people as a huge attack against the old way of doing religion and the living practice of mysticism in previous essays.

With Aquinas though, we have this war against mysticism taken to an extreme new level. The funny thing is that Aquinas is actually considered “mystical” by mainstream sources on the topic because he believed in Yahweh, and in his angels and in the miracles of the Bible quite literally. He also believed himself to be in contact with an angel that was providing him with inspiration for his work.

Now, this is the first part in today’s essay where I digress in any way from standard university teaching on the topics because I argue that they are using lax and incorrect terms and definitions. Again: modern definitions of atheism and religious belief only serve to confuse, not enlighten us. Since we all essentially start from the default position of being mysticism deniers in our modern society, we simply label pretty much everything in society prior to the 1960s as “mysticism” and/or “superstition”. But there’s a lot more nuance to the topic, as I hope that I have already demonstrated in the essay series so far.

So, for example, we have a similar case with Socrates who also believed he was channeling the will of some kind of a spirit (an angel or daimon). But he was also part of a coup of violent “atheists” who outlawed the religious traditions of Athens upon coming to power and was eventually executed for his preaching of “atheism” to the youth. With modern definitions, Socrates is simply thrown into the same bucket as a Siberian shaman or a Crowley devotee or a Confucianist or an Islamic simply because he had some residual belief in non-material realities/entities, and that is enough to get you labeled a crank, a mystic, a superstitionist or w/e and disregarded by all of polite society nowadays.

Thus, Aquinas can’t be compared to a modern kind of Bill Nye the Science Guy or a Reddit user, true.

Bill Nye is an ethnic scientist.

But, I believe that he can be best described as a crucial in-between stage; a general advancing the front in the long war against mysticism several trench lines forward. Specifically, Aquinas limits and redefines acceptable mysticism to the confines of interpretation of Aristotelian and Hebraic scripture. To the use of reason (left brain) as opposed to intuition (right brain) which is misapplied to metaphysical fields of inquiry.

Also, he sort of reveals the whole game when he frames his revolutionary approach to religion as being opposed to “paganism”. I put the term in quotes because most people interpret it to just mean belief in many gods. That’s barely even scratching the surface though and a better definition will be supplied and fleshed out as this series continues and we start digging deeper into actual pagan religious practices, their worldview and why it was so violently opposed by our cabal of villains.

Aquinas:

Aquinas actually believed in magic as well, is the thing.

At the time, so did the Churches of both East and West, and the peasantry of Europe practiced it in the countryside despite the campaign of repression waged against it by the Church. Here, again, terms and definitions have simply been changed and so meanings have been obscured by propaganda and modern sensibilities. That which was normal and pagan suddenly became labeled “dark/black/demon magic” or just “magic” and “sorcery” in general. But all of these so-called “demonic” practices have their root in native European cultural traditions and in pre-Abrahamic practices found all over the world.

Put simply: Aquinas did believe in magic, he just thought that magic came from an evil source.

Like, for example, he gets into a heated discussion on the nature of werewolves in the Summa Theologica wherein he argued that the source of the phenomenon was infernal pagan magic designed to trick Christians into doubting the Bible.

No, really:

Put another way: Aquinas believed in werewolves, he just didn’t like them on account of them refusing to worship Yahweh.